What is horror? As a genre, I mean. I thought this would be an appropriate question for this year’s Halloween post. Also, I’ve been following James Smythe’s ongoing series “Rereading Stephen King” in The Guardian, and it’s been a trip down memory lane for me, allowing me to reflect on the genre in ways I didn’t when I was really reading a lot of it as a teenager.

Before I leap into the discussion though, I feel it’s important to point out that horror fiction has seen better days. Zombies and vampires may be big on TV, but — in so far as there are bookstores left — there really aren’t many shops that have a whole section devoted to the horror genre, certainly not in the way they did in the 80’s (which was “horror’s boom time,” according to the Horror Writers Association).

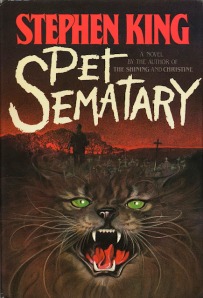

At one point in his ‘reread’ of Pet Sematary, Smythe notes, “Horror has something of a bad reputation these days, surrounded by constant claims that, as a literary genre, it’s on its last legs: there are, after all, only so many ways you can tell a ghost story.” There is a continuing non-mainstream fan base, of course; thriving offshoots, such as Weird; and Stephen King and Anne Rice were on the cover of Costco Connection this month, but the scene is nothing like it used to be.

At one point in his ‘reread’ of Pet Sematary, Smythe notes, “Horror has something of a bad reputation these days, surrounded by constant claims that, as a literary genre, it’s on its last legs: there are, after all, only so many ways you can tell a ghost story.” There is a continuing non-mainstream fan base, of course; thriving offshoots, such as Weird; and Stephen King and Anne Rice were on the cover of Costco Connection this month, but the scene is nothing like it used to be.

Partly that’s because of the limitations of the genre, mired as it is in gothic tropes, cliches as old as folklore, and repetitive scare tactics. The great flourishing that began in the 70’s now seems stultified. Perhaps it never was a cohesive genre in the way that mystery novels are, but certainly, for a time, it seemed to be.

Yet horror never struck me as limited to horror tropes. It’s not about werewolves, witches, or wyrms. It’s not about spooky thrills, at all. Instead, the genre is defined by that heart-hammering, head-expanding feeling one gets when reading something that goes beyond fear into something more disturbing. Smythe summarizes this well:

Coming back to [Pet Sematary] after nearly 20 years, I was faintly nervous. I remembered how the book made me feel, even if I didn’t necessarily recall its content. It’s curious: scares don’t stay with me, not really; but horror (something that makes you question beliefs, emotional and moral responses, yourself even) hangs around.

In an interview at Electric Lit, Victor LaValle nailed what really causes this feeling. He said that real horror is the realization that “there is a God and it’s not there.” His example of a real monster was The Nothing from The NeverEnding Story. “To me that’s terrifying to contemplate. By comparison, even H.P. Lovecraft’s Old Gods mythos is too optimistic.”

The revelation ‘there is God that is not there,’ which is not the same thing as there being no God, is horror because it sits in your brain and you can’t shake it off or make light of it. Call it a wake-up call. Horror in fiction, in its purest form, is an attempt to rip back the covering on the things in life that we most desperately want to avoid, to give the reader the experience of what Kurtz felt at the end of his life in Heart of Darkness:

Anything approaching the change that came over his features I have never seen before, and hope never to see again. Oh, I wasn’t touched. I was fascinated. It was as though a veil had been rent. I saw on that ivory face the expression of somber pride, of ruthless power, of craven terror—of an intense and hopeless despair. Did he live his life again in every detail of desire, temptation, and surrender during that supreme moment of complete knowledge? He cried in a whisper at some image, at some vision,—he cried out twice, a cry that was no more than a breath—

“The horror! The horror!”

Horror is the only genre of escapism that doesn’t let the reader escape, the only one in which everyone dies in the end. As Chuck Palahniuk put it in Fight Club, “On a long enough timeline. The survival rate for everyone drops to zero.” Horror is the genre that makes us feel the truth of that statement in our bones.

People want and need ‘the horror’ because it helps to spend some time mentally wrestling with reality’s starkest secrets and grimmest moments in advance of having to actually deal with them directly. And that is not something that is limited to the genre of horror at all.

There is very little that is scary anymore about Dracula. Or the mummy. Or Frankenstein’s monster. We’ve seen it all before. And “horror has once again become primarily about emotion. It is once again writing that delves deep inside and forces us to confront who we are, to examine what we are afraid of, and to wonder what lies ahead down the road of life” (from that essay by the Horror Writers Association again).

But is it any wonder that readers, faced with the bleak frontier of a genre removed of the trappings of ghosts and goblins they love, have abandoned it for other forms of escapism. Because, in the final analysis, true horror is hopelessness. And I’ll take a good old Jack-o’-lantern over that any day.

Happy Halloween!